From the 19th Century to Today: Egypt and Islam (PART ONE)

.png)

Egypt and Islam: From Reform to Control (19th Century-Present)

The relationship between the Egyptian government and Islam has been a complex and shifting one since the 19th century and the beginning of the secularization of the country. Before the 19th century, Egypt applied Sharia Law for every matter, and there were hundreds of religious schools (Kuttab and Madrassa) around the country. The Islamic model was the only one for the Muslims (Christians had their own courts and schools). In the 19th century, Shari’a law got more and more confined to personal matters (heritage, marriages and divorces, etc.); a national court of law developed in parallel to Sharia courts; then the national public school system appeared, which pushed to the side the Islamic school system (and teachers initially all from an Islamic teaching background were replaced by teachers with a nationalist secular teaching); other secular universities (inspired by the European system) were developed aside from the Islamic university of Al-Azhar, etc. Religious madrassas and kuttabs were closed, only for Al-Azhar to remain as the main religious institution (out of dozens of huge madrassas). Egypt needed to “modernize,” and so it did by following the European colonial system. There were even French and British Christian missionary schools developed for the Europeans who lived in Egypt and for the children of rich Egyptian pashas (even Muslim ones). Hundreds of Egyptians were sent to study in Europe and came back praising the European model. Thousands of Europeans lived in Egypt (1 500 000 by 1930); some worked for the Egyptian government, and others were from the economic elite and made Alexandria and Cairo cities similar to European ones with banks, stock exchanges (among the first in the world), alcohol, theatres, operas, nightclubs, cabarets, and even prostitution. A lot of the Egyptian elites were English or French speaking, secular, and not really religious (contrary to poorer classes); some were Freemasons, and pushed for a modern Egyptian state. Although some were nationalists and independentists (Egypt being a British colony from 1882 to 1922), their models were still European countries, and they saw Egypt as part of Europe.

Al-Azhar was (and still is) the most important religious institution in Egypt. In the 19th and 20th centuries, teachers were all from Al-Azhar, but as more secular institutions were created, the institution’s influence waned over time. Some of al-Azhar’s thinkers were supportive of the European ideals of modernization being applied in the country, such as Rif’a al-Tahtawi or Muhammad Abduh (both lived in Paris at some point). For them, those were not in contradiction with Islam. Al-Azhar also stood by the king; as they tried to make King Fuad the caliph after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. This situation (Europeanization, lack of religious pushback, liberalism, the fall of the Caliphate, etc.) prompted a teacher, Hassan al-Banna, to found the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928, an organization that wanted to push back against European influence, bring back the true Islam, in its orthodox and traditional essence, as the pillar of Egyptian society and unite Muslims. He wanted to do so by Da’wah and Education, the goal was to “re-islamize” the masses so they can influence the government. With its charities, radio, and newspapers, the organization grew quickly, reaching 450 000 active members across the country in less than 20 years, becoming one of the most important political groups in Egypt. But the popularity of the Brotherhood was seen as dangerous; they had members in the police and the army and had also managed to gather money and volunteers to fight against Zionists forces in the 1940s and more so in 1947, which alarmed the State. That's why in 1948, el Nokrashy (then prime minister of Egypt) banned the organization, seized its assets, and jailed several members. In reaction, a member of the brotherhood assassinated him (from his own decision and against the wishes of al-Banna); in retaliation to the attack, al-Banna was also assassinated.

Gamal Abdel Nasser: Full Secular Control

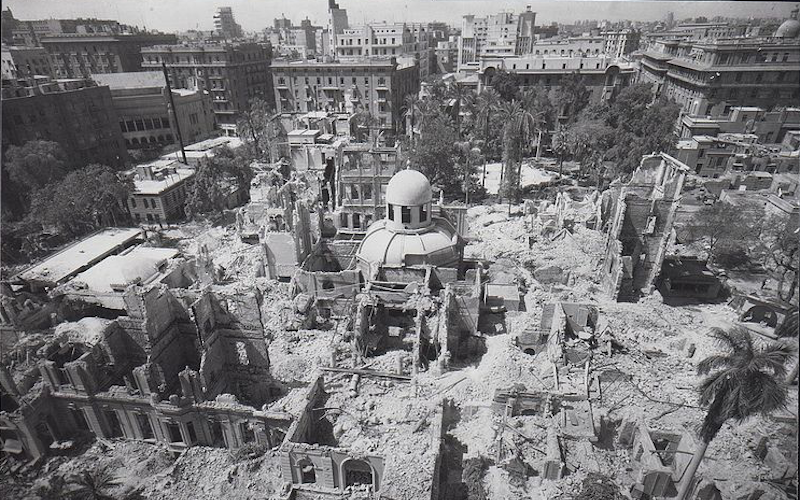

In January 1952, the people had enough of the elites with their lavish lifestyle and the European domination (the British army had just massacred 52 Egyptian policemen in a firefight), and so the great fire of Cairo started. In a single day, hundreds of buildings (hotels, bars, cinemas, shops, restaurants, etc.) of the elites (Europeans and Egyptians) were burned, 26 people were killed, and 552 were injured. In July 1952, a group of officers (“the Free Officers”) made a coup that overthrew the monarchy. This group of officers was composed of nationalists, communists, socialists, and even a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. The group now in power promised democracy and tried to negotiate with different political forces (the Wafd, feminists, communists, etc.) and got quite close to the Muslim Brotherhood (Nasser attended events, Sadat said he was admirative of Hassan al-Banna and visited his tomb with Nasser, etc.) and socialists, with whom they had contacts and negotiated until they decided to fully take power. Gamal Abdel Nasser became president, purged the army of any dissidents, banned all political parties, and closed

all independent media, and in 1954 declared the Brotherhood a terrorist organization (for an alleged assassination attempt on his life, though the Muslim Brotherhood always claimed it was a false flag attack made by Nasser himself), thousands of opponents were jailed (with or without trials), and he built camps for political prisoners.

During his time as president, Gamal Abdel Nasser enforced socialism, secularism, and pan-Arabism, which wanted to unite the Arabs beyond their religious differences, whether they were Christians, Sunni, or Shia. So religion wasn’t his priority, but as the leader of a Muslim country, he still needed to control Islam and wanted to show that socialism didn’t contradict Islam (he did a whole speech about that, blaming the Saudis for saying such things because they feared for their wealth). That’s why he started huge reforms to assert state control over religion. In 1956, he abolished the independent Sharia courts that existed parallel to the National Judiciary system. In 1957, he nationalized all the Awqaf (some already belonged to the state, but now all the Awqaf (pious endowments) of the country were under direct state control). In 1958, Gamal Abdel Nasser abolished the council that elected the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar and instead made it a direct presidential appointment.

The first Imam of al-Azhar (head of the university and historical institution, its highest representative) nominated by Nasser was Shaltut, someone known for his reformism and his view that Shia are a legitimate Islamic school (which he stated explicitly in his fatwa of 1959). As Nasser sought to unite the Arabs irrespective of their religions, nominating someone who wanted to reconcile Sunni and Shia as head of the highest Egyptian Islamic institution was a strong move to defend his Arab union. In 1961, he made the Al-Azhar reform, making it a state-owned university under the control of the Ministry of Awqaf. This reform was opposed by several Azhari teachers. In the end, Nasser fired 128 opposed Azhari teachers from their positions in the university (there were 298 teachers at Al-Azhar University when Nasser took power), replacing them with new, younger ones. The counterpart for that loss of autonomy was heavy investments from the government, allowing Al Azhar University to have a huge new campus, which meant more students, bigger wages for teachers, and several missions around the world. Wary of the speeches of the Muslim Brotherhood in mosques, Gamal Abdel Nasser also asserted his control over mosques, they now had the same khutba’s subjects picked by the ministry of awqaf (it’s still the case to this day), and were of course under surveillance by the state. Nasser now had full control over the religion in Egypt, and so he asked the Supreme Council of Islamic Affairs (which he founded) to publish articles and make speeches defending the fact that socialism is Islamic, while Al-Azhar made fatwas supporting his policies. The media (radios or newspapers, all under state control) were also important in conveying those fatwas and publishing cartoons of Nasser triumphing against “terrorists” (the terrorists being the Muslim Brotherhood).

Nasser saw the Muslim Brotherhood as a threat and one of his worst enemies (in the country); therefore, he had little pity for them. Hundreds were condemned to the death penalty by martial courts, and thousands were jailed and tortured regularly and in different kinds of ways. In the military prisons, Shams Badran and Hamza al Bassiouny became famous for the way they tortured political prisoners; it varied between whipping, burning, hanging, drowning, and attacking with dogs. Daily humiliation was normal under their rule of the jails. There is a story of a wife who, after months of pressure, managed to finally get the right to visit her husband in prison. She went with her daughter, only to find Hamza al Bassiouny holding a leash and making her husband bark and behave like a dog. One of the Muslim Brotherhood leaders remembered, “As I was being tortured, I said to Shams Badran, ‘Fear God!’ and he replied, ‘I’ll put God in the cell next to you if he comes down here.’” Blasphemous quotes weren’t rare from torturers (and even to this day); they have no sense of sacredness and want to break the prisoners by breaking their faith and humiliating them. The harsh conditions in prisons, the ideological vacuum caused by the prison's isolation from the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood, and the delusion that the members of the Brotherhood experienced prompted some to have more “radical thoughts.”

Sayyid Qutb was one of those important thinkers that adopted a harsher discourse after his imprisonment; he (like most of the Muslim Brotherhood) had a lot of hope in Nasser and the Free Officers movement before being jailed and tortured like thousands of Brothers. While in the prison hospital, he wrote several books and exchanged them with brothers from other prisons that were treated in the same hospital; thus, after they were healed, they went back to their respective prisons and spread Qutb’s thoughts on the State’s “Jahiliyya” (it refers to the “period of ignorance” of pre-islamic Arabia) and the government of Nasser as being evil and un-Islamic (though he never made takfir explicitly on Nasser). In 1957-1958, the lower ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood were released (some weren’t even charged to begin with and spent 3 or 4 years before being released) and reorganized around Qutb ideology and thoughts until they were arrested again in 1965 and brought to trial for “conspiring against the state,” and some were hanged (Qutb himself was executed). The female section of the organization, the Muslim Sisterhood, was also targeted (which wasn't the case before), and someone like Zayneb al Ghazali was condemned to 25 years of harsh labour, jailed, and tortured. This second wave of persecution caused a division within the Brotherhood, with some following their leader, al-Hudaybi, and others claiming to follow Qutb’s ideas (they went even further than Qutb and made takfir). Al Hudaybi distanced himself from the thoughts of takfir, which prompted some members to leave and reject the Muslim Brotherhood. The Qutbis thought that they couldn’t negotiate and collaborate with an un-Islamic state and called for revolution, whereas al-Hudaybi wasn’t a revolutionary and thought the way to go was gradual changes by da’wah, education, and political involvement, just like al-Banna before him. Al Hudaybi made several official statements while in prison to refute the “radical thought” and to call for a more “moderate vision.” Debates rose about who really wrote those statements, but they claim one thing: several scholars of Al Azhar were consulted to write it, which means that the state was informed of those “radical thoughts” in prison and wanted to refute them using Al Azhar's knowledge of Islamic sciences (because the books of Qutb were widespread even though they were banned by the state). That’s a particularity of Arab countries: the state (which is secular, though differently from Western countries) uses modernist thoughts and Muslim scholars against “political Islam.” This is a recurring trend in Egypt’s modern history and relation to Islam.

Anwar al-Sadat’s Legacy

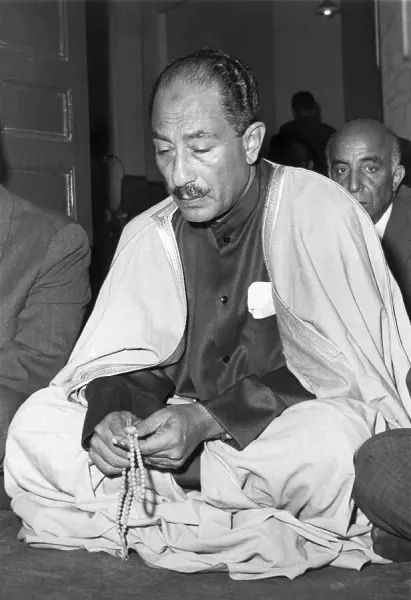

Nasser died in 1970, and the vice president, Anwar el Sadat, took power. This period is crucial for the history of Islam and Egypt. There are several trends: the return of the Muslim Brotherhood, student organizations, the state using Islam, and the emergence of different Islamic movements.

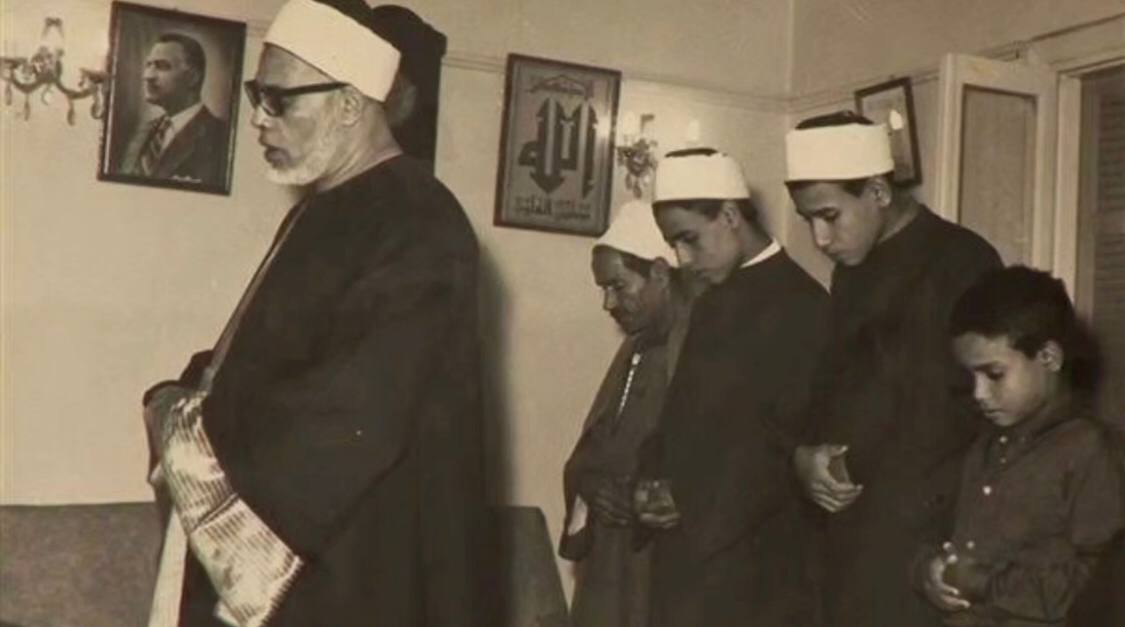

Sadat was not a socialist; on the contrary, he slowly wanted to get rid of them. He saw “Islamists” opposed the left (socialists and communists), and he supported them and tried to co-opt this religious side with some state slogan like “al ‘ilm wal iman” (science and faith), and the state media called socialists and communists “atheists” and “foreign agents” (meaning USSR agents, as Sadat disliked the Soviet Union). He even purged socialist members of the old regime. Pushing out the socialists made a huge political vacuum in society, which was filled by Islamists. Although Sadat wasn’t one, he still allowed them to prosper and presented himself as a religious leader with symbolic moves, quoting the Quran and making religious references in speeches, inscribing Sharia as “inspiration for the principles of the constitution,” making a law against apostasy, and making a law in 1977 to prosecute blasphemy and speeches that go “against the family values of Egypt.” Even the war songs changed from a pan-Arabist tone to a religious one, with “Allah Akbar” being the main song of the Egyptian army during the 1973 war. This war was portrayed by the state as Jihad, and the operation was called “Operation Bar,” but when the government made peace with the Zionists, it was labelled a matter of national interest. The government trained and sent weapons to Afghan fighters after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (1979); the government even let Egyptian volunteers join the fight, and several books and speeches were done supporting islamically the Afghan struggle against the Soviets. Religious and “Islamist” people were in all sectors of the society, trade unions, student organizations, Islamic charities, Islamic private clinics, media (newspapers, radio broadcasts, cassette tapes, books, TV), etc… The 1970s was the beginning of religious “stars.” Several preachers had their fame boosted more than their counterparts from the start of the 20th century due to media support, such as Kishk, el Metwalli al Shaarawi, Mustafa Mahmoud, and so on… They gained millions of listeners throughout the country. (To this day, Al-Shaarawi’s pictures are everywhere in Egypt). From 1971 to 1981, there were dozens of independent monthly Islamic magazines, some reaching an educated audience, whereas others were more accessible.

Student organizations played an important part in Egyptian politics. Before Nasser, they were vocal, and thousands of students protested against the British and even trained militarily on campuses before going to fight the British along the Suez Canal or the Zionists in Palestine. They were, of course, politicized, with student organizations representing the communists, the Wafd, or the Muslim Brotherhood. Nasser made a crackdown on the student organizations and only allowed his own Socialist organization, with guards patrolling on campuses, making sure no other political expression was on campus. But after the humiliating defeat of 1967 during the 6-day war, students rose up and protested in 1968, demanding more political freedom and rejecting the government ideology. With Sadat in power, the government wanted to crush the leftist student organizations and tried to manipulate a student organization called “Shabab al Islam” (the Youth of Islam), founded in 1972. Shabab al Islam was an Islamic politicized organization influenced by the ideas of the Muslim Brotherhood but using leftist activism tactics. This organization did all it could to remain independent from the government (officials offered money and met several times with the leaders of the organization); the government put pressure and tried to manipulate and use the organization to violently attack the leftist students (which Shabab al Islam disapproved of and refused, but the government did anyway using other Islamic student organizations).

The Islamic student organization was critical of the government and leftists; they were against the USSR and criticized the government's inaction towards Israel, which occupied Sinai. They published newspapers and statements, held conferences about Egypt and about the persecution of Muslims around the world, protested, etc. In 1974, most of the members of Shabab al Islam (which at its peak was at least a thousand) joined a new organization called “al Gama’ah al Islamiyyah.” Al Gama’ah al Islamiyyah was mostly students from a peasant background who received a religious upbringing and, with the reform of Sadat, were now studying at the Universities of Cairo and Alexandria but also in their own cities from the countryside. It started as “Al Gama’ah al Diniyyah” (the religious society) and at the beginning focused only on religion (praying on campus, etc…), with very few members (one of them recall being only 2 to pray in his faculty) it evolved and became present everywhere, they debated with leftists and consulted scholars on how to answer them, they published articles, held public talks, they had a small religious curriculum for their members (teaching Juzz ‘amma, 15 out of the 40 ahadith of al Nawawi, fiqh and tafsir, etc…), held protests, weekly islamic book fairs on campuses, sold hijab, organized charities, sports clubs, and even summer camps, with Azhari students and prominent scholars like Muhammad al Ghazali or al Qaradawi being invited to give lectures during those camps that gathered thousands of students across the country. They even had a female section, which received talks from Zainab al Ghazali, and they provided female-only buses for students of universities. They had a structure with a leader (amir) and a council (shura) in every faculty and university. They spread to almost all universities and faculties of Egypt and won the student union elections in almost all of them for several consecutive years. The student union was important because it had money, which the Jama’ah al Islamiyyah used for several things, one of which was to finance Hajj or ‘Umrah for around 100 000 Egyptian students. The Saudis sent free books with those students returning to Egypt, spreading Salafism.

Al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah took a more political discourse over the years, making public statements and conferences on political subjects and opposing the government on several matters: the non-application of Shari’ah by the government and the peace talks with the Zionists. In 1979, in response to a statement by Sadat that said, “There is no politics in religion and no religion in politics,” they organized a conference that gathered 10 000 students on the Cairo University campus and published a statement to oppose this. The same year, as the Islamic movement celebrated the revolution in Iran and made statements with “lessons to learn from Iran,” the Egyptian government welcomed the Shah in exile, which provoked a strong reaction from the Islamic movements with protests numbering thousands. From 1977 onwards, the government changed its tone towards the Islamic movements and became more wary of them. That year, a group named “al Takfir wal Hijra” killed the former minister of Awqaf, Muhammad al Dhahabi, and Sadat visited the Knesset and met the Zionist politicians in occupied Palestine, which drew harsh criticism from the Islamic movements. In 1979 the student union elections were restricted by the state (they excluded al Gama’ah al Islamiyyah from any election), and the government also brought back guards on campuses (which hadn’t been present since Nasser), and they made it more complicated for al Gama’ah al Islamiyyah to hold conferences and events. In 1980, summer and winter student camps were banned.

With all these measures, they saw that they couldn’t negotiate with the state (like they used to) and that the student activism was harder because of the state. They got closer to the Muslim Brotherhood, with whom they already had links (they invited several active or former members of the Muslim Brotherhood to give conferences), and so Islamic activism spread from universities to society. Some groups of al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah (such as the group in the Minya and Assiut campuses) were more conservative and opposed to the thinking of the Muslim Brotherhood; they were more aligned with the ideas of the Qutbis, they went underground and started to train students in the use of weapons, and they kept the name “al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah” when they fought the government. They benefited from the hierarchy, the links created between members, and the organization of al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah to plan their attacks.

Sadat let Al-Azhar have more freedom and nominated as Sheikh al-Azhar someone to whom the Muslim Brotherhood was sympathetic, Abd al-Halim Mahmud. He also gave advantages; he financed Al-Azhar, and the university started to welcome more and more foreign students. Sadat managed to get fatwas from al-Azhar supporting his economically liberal policies and his peace treaty with Israel in 1979 (which was heavily criticized by various Islamist groups). Under his presidency, the parliament passed a law requiring all preachers in mosques (on Jumuah) to be licensed by the state (ensuring the exclusion of opponents or “radicals”). Al-Azhar was still seen as completely under government control, which drew criticisms from all sides and discredited the institution; even graduates from the university, such as Kishk, criticized Al-Azhar. Some groups went even further and considered al-Azhar as being the religious arm of the government (a government they considered apostate), such as the armed group “al-Takfir wal-Hijra,” who kidnapped a former Minister of Awqaf (Muhammad al-Dhahabi) and executed him in 1977.

The relationship between Sadat and “Islamists” is a complicated one. He freed the Muslim Brotherhood in 1971 and even nominated 2 former Muslim Brotherhood members in his government. Quite extraordinary—after 17 years in jail, the Muslim Brotherhood didn’t die; on the contrary, they grew. But it wasn’t easy; thousands had been jailed or lived in exile and had to reconnect with their families and try to live a normal life in society after years of torture and isolation. Some of the former prisoners decided to isolate themselves from a society that doesn’t understand their struggles (some of them radicalized), others left Egypt for the Gulf countries where the Muslim Brotherhood was already installed, like al-Qaradawi, and others decided to remain in Egypt but had doubts about what role the Muslim Brotherhood could play in a more religious society than they experienced before jail. There were conflicting views within the Muslim Brotherhood, with people leaving the organization and creating their own (some created militant groups, while others created Islamic media); others felt a need for an organization teaching the texts of the Brotherhood with a strong hierarchy and even a secret organization to avoid any persecution, and others tried to combine both views.

The last one is the Muslim Brotherhood as we know it, with Tilmisani as the new leader in 1973. They created publishing houses to publish ancient books of the organization and new ones, and in 1976 a magazine called “al Da’wah.” This monthly magazine had several issues that reached 100 000 copies and were sold out; they also had 10 000 more copies distributed in the Arab world. The magazine spoke about the Muslim Brotherhood: their ideas and goals and their history (to respond to the dark image they got from Nasser’s propaganda and show their suffering and heroism); it also spoke about an Islamic society and the role of Islam (they presented the Muslim family and presented solutions to issues in the daily lives of Egyptians); international politics (critics of the West, the peace deal between Egypt and the Zionists, and struggles of Muslims around the world to remind the Muslims that they are part of a larger community); and critics of internal Egyptian policies and the government. The magazine maintained a peaceful discourse, stating that there is no compulsion to adhere to their ideas, but that didn’t prevent them from criticizing the state or even Al-Azhar, which, in their opinion, was speaking of “the steps of ablution, or they describe how to conduct the Hajj, but on usury, political oppression, and other violations of the limits of God, they are silent; it is as though these problems disappeared from their society or that Islam had made a pact of peaceful coexistence with them.” By criticizing the silence of Al-Azhar or even their support for the government’s decisions, they discredited Al-Azhar as an institution that doesn’t speak of the “real goals” of an Islamic society. The magazine was an opponent to Sadat, criticizing harshly several decisions: him getting closer to the West, his peace deal with the Zionists, welcoming the exiled Shah in Egypt, and the non-application of Sharia. But Sadat had some interests in letting the Muslim Brotherhood publish, as they recalled stories of torture and execution of their members under Nasser and criticized heavily Nasser’s politics and 1967 defeat. Sadat benefited from it by presenting himself as more tolerant, just, victorious, and overall better than Nasser, which allowed him to destroy his legacy and adopt radically different politics. But as years went by, Sadat was more and more criticized by different groups, and the Muslim Brotherhood went as far as asking him and his whole government to resign for “failing to implement and rule by the Sharia,” although they tried to avoid criticizing him personally and didn’t attack Sadat after his visit to Jerusalem in 1977 like other Islamist groups. In 1981, Sadat closed all the independent media and imprisoned thousands of opponents, some of whom were Muslim Brotherhood.

A Global religious phenomenon

As the influence of Al-Azhar was contested, there were also several other Islamic movements that started to emerge (or re-emerge) in Egypt at the time. There were the Salafis, who arrived from the Gulf with millions of Egyptian emigrants who worked and lived there for years returning to Egypt, and with finances from the Gulf states, who had a closer relationship with Sadat than Nasser. Books and cassette tapes of foreign Salafi scholars of the time, like Ibn Baz, Ibn Utheymin, and al Albani, were sold or sometimes even distributed for free on university campuses in Egypt. There was also the tabligh, originally from India; it was started in Egypt by a former Muslim Brotherhood. Released from prison in 1971, Ibrahim Ezzat took a different approach for the reform (islah) of the society. The tabligh’s goal is da’wah to Muslims; they want Muslims to practice Islam, and they don’t speak of politics, religious debate, or anything of the sort. It is difficult to estimate the impact they had, but nowadays it is estimated that there are 250 000 members in Egypt. Several people who came to practice Islam by the da’wah of the tabligh then went on to become scholars, Muslim Brotherhood members, or sometimes members of armed groups. Even Sufi tariqa experienced a revival during the 1970s (they never disappeared and weren’t persecuted, but their numbers rose considerably in those years); one tariqa, the Burhaniyya Desuqiyya Shadhiliyya, is said to have reached 3 million members in Egypt in the 1970s (out of 30 to 40 million Egyptians in those years).

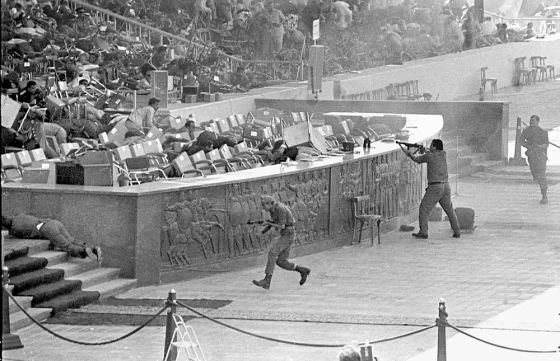

Several armed militant groups emerged under Sadat; their thoughts came from followers of Qutb, and they did different actions, attempted a coup d’état with members within the army (1974), assassinations (1977), uprisings (1981), etc… The reasons those groups hated Sadat and his government were several: first, he didn’t apply Sharia, so they made his takfir; on top of that, he negotiated, made peace, and recognized Israel; thus, he also got closer to the USA. Ultimately what prompted them to kill Sadat was his crackdown on opponents and critics of his regime in 1981. Thousands were arrested, amongst whom were several members of armed groups and student organizations. Independent media was banned, and freedom was restricted. The president, once called the “pious president,” was now called “pharaoh” (he even targeted and put under house arrest the Coptic pope who criticized him). But a cell in the army (wary of seeing a repression like Nasser’s) managed to slip through the crackdown and killed Sadat during the military parade of the 6th of October in front of the cameras of the world. 3 days later, around 75 former students from al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah rose up in Assiut, almost taking control of the city, killing more than 60 policemen and soldiers and injuring more than 90.

Mubarak: “War on Terror”

After the assassination of Sadat, his vice president, injured in the attack, took power and declared a state of emergency (which provided more power to the police and the army); it would remain in place until 2011. This meant that police used torture and could beat people to death without any consequences; all of this was justified by a “War on Terror” even before the Americans started those practices under the same justification. But let’s talk about how it gradually took place.

After being sworn into office, Mubarak had to deal with a lack of legitimacy and pressure from the American ally, so he embarked on a “democratic” path in form but not in reality; there were parliamentary and presidential elections, but they were controlled. He freed the political prisoners of Sadat and even met some of them (although he didn’t meet the Muslim Brotherhood leader after releasing him because “that would upset Washington”) and wanted to unite the people and political parties against the “Islamist” violence. He also didn’t want to oppose political parties that had a lot of popularity.

The Muslim Brotherhood had a complex relationship with the government. They were Islamists but pledged to not use any violence, which prompted the government to try and use those “moderate Islamists” so they could co-opt the radical ones and delegitimize violent groups. The goal of the government was to make the Muslim Brotherhood a controlled opposition, and the goal of the Brotherhood was to win politically. Although the independent press was reauthorized in 1984, that wasn’t the case for al-Daw’ah; the publishing license of the Brotherhood magazine was not renewed by the state. But in counterpart, the Muslim Brotherhood was allowed to participate in parliamentary elections in 1984 but only under the name of the Wafd (a secular political party). When the General Guide of the Brotherhood died in 1986, an official delegation sent by the president was present at his funeral. However, relationships would change with the parliamentary election of 1987; their Islamist coalition ranked second place (after the government’s party) and grabbed 60 seats (36 were Brotherhood) and got 17% of the votes. For the first time in the history of Egypt, Islamists were in the parliament with their own party. Mubarak feared the popularity of the Muslim Brotherhood and dissolved the parliament with a false pretence. The Muslim Brotherhood saw that they couldn’t compete in parliamentary elections, and so they went to challenge the government with elections of syndicates. There were 3 million members of syndicates in Egypt, so those organizations were an important political platform, and the Brotherhood dominated it. The Muslim Brotherhood vividly opposed the intervention in Iraq in 1991, during which Egypt sent 40 000 soldiers in the coalition. They were the most powerful opponents to the government, and the government feared them as they had little control over them. The Salsabil affair in 1992 accelerated the break-off. Salsabil was an internet company that signed deals with the army and secret services, but the government accused the company of being a facade for Muslim Brotherhood intelligence activities and said that the Brotherhood wanted to use information gained by espionage on the army and government to take power. The whole company (owner and employees) was imprisoned. In 1995, after an assassination attempt on Mubarak’s life, the government accused the Muslim Brotherhood of being related to the attack and raided an official meeting of the Brotherhood, arrested the leadership of the Brotherhood, and tried them by military court, which condemned all 63 accused to 3-5 years in prison. In 2000, the Brotherhood participated in the parliamentary election as independent candidates (as they were banned as a party) and won 17 seats (more than any opposition party). In 2005, under pressure from the streets with protests and pressure from the USA for more democracy in Egypt, Mubarak allowed for a free and fair parliamentary election; he thought he would easily win, and no opposition party would have more than 20 seats. The fact is, the Muslim Brotherhood ran a huge campaign; they changed some opinions, notably about the Christians, and promised to make their lives better. They presented 150 candidates (who participated as independents) and won 88 seats. The government was shocked, and they intervened after the first round of election to manipulate it, thus avoiding giving around 128 seats to the Brotherhood. Seeing the “charm campaign” the Brotherhood did towards the Christians, the government changed the Constitution, notably the 1st and 2nd articles, which stated “Egypt is a Muslim state” to “Egypt is a citizenship state.” This allowed women and Christians to potentially become president and the government to ban religious parties, which evidently targeted the Muslim Brotherhood, who walked out of the parliament during the vote in protest. In 2006, students of Al-Azhar University, who were Muslim Brotherhood members, organized a “sport event,” according to them, whereas for others it was a military parade on campus and almost seen as a training camp for Jihad because the students wore masks. The government used the “military parade” to ban and crack down heavily on the Muslim Brotherhood and arrested hundreds. Their goal was to break the Muslim Brotherhood and prevent them from having any power, so much so that in the 2010 parliamentary election (which was rigged, and there were cases of thugs intimidating people who voted for opponents), there was only one Muslim Brother who managed to grab a seat (as an independent). This crackdown prompted the Muslim Brotherhood to join the protests in the 2011 revolution, although they hesitated at first because they didn’t want to be associated with any protest; the only one they mobilized heavily for was in 2008 for the War in Gaza.

After the assassination of Sadat, Mubarak arrested 4000 “radical Islamists” and tried to use Al-Azhar by making a public “prison dialogue” on TV between scholars of Al-Azhar and prisoners to refute and discredit the Islamist view. However, the dialogue failed as prisoners were either rejecting the scholars or mocking them, saying, “Release me, for I have been reformed by the guidance of the scholars.” That’s when the government understood Al-Azhar lost most of its legitimacy, and the government called for the “moderate” Muslim Brotherhood to lead this prison dialogue, as they were more accepted by the people and “Islamists.” The increased control the government had over Al-Azhar undermined the legitimacy of the institution and didn’t help the government or the institution. So throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the government allowed more independence for Al-Azhar to preserve its reputation and legitimacy as an institution. They could allow this, as Al-Azhar had a common enemy with the government, who challenged their legitimacy. Jad al-Haq, grand imam of al-Azhar from 1982 to 1996, tried to refute the Islamists who attacked the legitimacy of al-Azhar, writing on the importance of knowledge and scholars in Islam and how scholars are superior to those who aren’t, and tried to argue that the government mostly did its job by preserving Islam and that Islam thrived in Egypt. Jad al Haq said, “Those who [commit violence] are not Islamists and do not represent Islam. They are criminals who must be punished. Every individual who challenges public order and the state's authority and power must be punished. Such an individual is not an Islamist at all. Those who make mischief in the land are the enemies of God and his prophet.” The government’s goal was to physically crush the Islamists, while Al-Azhar’s goal was to crush them theologically.

By 1992, al-Azhar had a lot of autonomy and could have independent opinions that opposed the state and went even as far as to criticize the government. In 1994, the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development was held in Cairo, a week-long discussion that was supposed to be a huge boost for the image of Mubarak, but the draft of the conference, which defended the right to premarital sex, homosexuality, and abortion, was rebuked and heavily criticized by Al-Azhar, which embarrassed Mubarak as most of the international press talked about Al-Azhar. Al-Azhar also put pressure on the government to ban works they accused of blasphemy, and Al-Azhar even issued a fatwa that called Farag Foda (an Egyptian “intellectual”) an apostate; two weeks after the fatwa, he was killed by “Islamists.” Whereas Mubarak tried to protect “culture” and “intellectuals” and their free speech, Al-Azhar asked the Egyptian Council of State for jurisdiction over censorship about religious matters, which was granted by the Council (which came as a shock, but there were several “moderate Islamists” in the council). Mubarak was embarrassed by the ruling but didn’t overrule it, as he didn’t want to prove the point made by “Islamists” that Al-Azhar was completely under government control and had no authority. However, in 1996, the “independent” Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, Jad al-Haq, passed away after leading Al-Azhar for 14 years, meaning Mubarak had to choose a new Grand Imam. He appointed the former Mufti of the Republic, Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy, a pro-government scholar who opposed the view of the former Grand Imam on several things, in support of the government. For example, he supported abortion under certain circumstances, said that banks have the right to ask for interest under Islamic Law, and defended the acceptability of alcohol and casinos for foreign tourists in Egypt. “Islamist” and “conservative” scholars of Al-Azhar were highly critical of him, whereas the government, “progressive scholars,” and intellectuals saluted his views. After his appointment, he purged Al-Azhar of dissidents and “conservative” voices and wanted to depoliticize Al-Azhar. Scholars who criticized him for meeting an Israeli rabbi were forced to resign from their official positions and replaced with pro-Tantawy scholars. By nominating Tantawy, the government asserted its dominance over Al-Azhar because they lost control over other sectors of the society and had enough of the criticism of Al-Azhar, an institution they used to completely control.

The militant groups were the most active during the Mubarak era. They made at least 700 attacks, which killed 2000 Egyptians between 1982 and 2000. They targeted precise groups of people: tourists, government officials, policemen, soldiers, and secular intellectuals. In 1995, they even tried to assassinate Mubarak during a visit abroad. Some groups had deep roots across neighbourhoods in Cairo, like Imbaba, a poor neighbourhood deeply impacted by an earthquake in 1992; the “Islamists” took upon themselves to help the people who were abandoned by the state. They had de facto control over the 1 million inhabitants of the neighbourhood, and the government had to send 12 000 soldiers to fight and take back control over Imbaba. After a violent day, they arrested thousands of members, amongst whom there were 150 leaders of different militant groups. The government also invested heavily in the secret services, who infiltrated and took down cells from the inside but also collaborated with foreign secret services like the CIA to arrest Egyptian “terrorists” abroad, bring them back to Egypt to interrogate (and torture them), and in some cases even execute them (extrajudicially). Former CIA official Robert Baer said, in Stephen Grey’s America's Gulag, “If you want a serious interrogation, you send a prisoner to Jordan. If you want them to be tortured, you send them to Syria. If you want someone to disappear—never to see them again—you send them to Egypt.” By the end of the 1990s, most armed groups (most notably al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah) declared giving up on violence; others joined international organizations like al Qaeda (which had several Egyptian leaders) and continued sporadic attacks throughout the 2000s.

The 2011 revolution: the eruption of anger of the youth

On the 25th of January 2011, thousands took to the streets in Cairo and overpowered the police security apparatus. Protests under Mubarak weren’t uncommon, but this time, they would change history. Inspired by the Tunisian revolution, which ousted Ben Ali just 11 days prior, thousands had gathered to protest the economical situation, unemployment, corruption and embezzlement (by the Mubarak family and their friends; their fortune was in billions of dollars), and police torture and brutality, which killed a man called Khaled Said (he was disfigured by policemen who beat him to death in June 2010; he became the symbol of this police brutality and lack of accountability). They protested the dictatorship and the rumours that Hosni Mubarak wanted to give the power to his son, Gamal Mubarak, after 30 years of rule and rigged elections. What started as a few thousand grew to thousands more after each day, and the government lost the plot. Police brutality was shown on TV, with police cars ramming into protesters, several policemen beating unarmed protesters on the ground, police dragging protesters beaten unconscious, and sometimes even the use of live bullets.

The government’s answers were desperate; they cut off the country’s internet for 3 days (attempting to stop social media and its influence), they staged pro-government protests (which turned to riots with anti-government protesters), they even tried to make promises of reform, and Mubarak promised that he wouldn’t be a candidate in the next presidential election, but nothing stopped the revolution. The army deployed in the streets, but seeing the power of the movement, they remained neutral and claimed to protect important sites only (museums, power stations, etc.). At first the Brotherhood was neutral and said, “Our members can go independently to those protests if they want, but they don’t represent our group,” but later they joined officially and mobilized hundreds of thousands across the country. By February 11, the government announced that Mubarak stepped down (highly pressured by the army) and that a transitional government would be created by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF). Al-Azhar at first had opposed the revolution (even though hundreds of Azhari imams joined the uprising). But after the government was toppled, they applauded “the will of the Egyptian people.” During those 18 days of protests, millions took to the streets, more than 800 people were killed, and 12 000 were arrested. But violence didn’t stop after the ousting; the situation was dire, a curfew was put in place, army checkpoints were still in the streets, weapons were easily found on the market, protests and clashes continued against the police, and as 21 000 prisoners escaped (in suspicious prison breaks) during the revolution (some were political prisoners, others were dangerous ones), insecurity was at its peak. Policemen and members of the secret services either fled the country (as they feared to stand trial for torture or killing), or others stayed in Egypt but deserted their posts, fearing reprisals. Dozens of police stations were looted and burned, their weapons now in the hands of random people. Some argued this, and the prison breakout was a deliberate act of the government to instill insecurity and fear and prompt people to support the authoritarian government that maintained “peace” and security.

From a chaotic revolution to a new beginning

After the ousting of Mubarak came almost a complete freedom of speech, as the government was only there for transition. The SCAF suspended the constitution and dissolved the parliament. It then organized a committee tasked with writing a few articles of a new constitution and organized a referendum about the new constitution, which, if accepted, would start a parliamentary election in 6 months and then a presidential one. The Muslim Brotherhood called their members to vote yes in the referendum, whereas liberals opposed it, as they thought they needed more time before competing in elections against the Muslim Brotherhood, who already had a program and an organization.With a 44% turnout, the referendum was adopted with 77% of votes for "yes." However, internal dissension (which started prior to 2011) rose again, and several leaders of the Brotherhood left to create their own Islamist party, while the Brotherhood created the “Freedom and Justice Party.” The goal of the Freedom and Justice Party was to appeal to non-Islamists and present as more “moderate.” Morsi said, “It is not an Islamist party in the old understanding; it is not theocratic; it is a civil party.” Egypt is a “civil democratic state with an Islamic reference,” especially in law. The party “guaranteed the rights of Christians and their freedom of belief and worship according to their laws and rules, in addition to safeguarding their litigation through Christian laws and rules in their private affairs.” and they emphasized the equality of all people. The party’s program spoke about corruption, justice, security, economy, development, cultural and religious leadership, etc… In total, 67 different parties existed and competed for the parliament. The FJP allied with 40 parties at first, but in the end they formed a coalition of 11 parties in the “democratic alliance” with the slogan “We bear good for all of Egypt” (they didn’t use their old slogan “Islam is the solution” nor call themselves the “Islamic alliance”).

Three other coalitions emerged: “the Egyptian Bloc,” “the Islamic Bloc,” and the “Revolution Continues Alliance.” Some small parties competed independently in the elections. While the two other coalitions were secular, the “Islamic Bloc” were “hardline Islamists”; they were Salafis, and if at first they called the revolution “a rebellion against the state” and refused to partake in it, they still created their political parties and wanted to benefit from the situation. The “Al Nour Party” and the “Building and Development Party” came from important groups: the Social Salafi Call (which possessed Salafi TV channels, publishing houses, etc.) and Al Jama’ah Al Islamiyya (the former armed group and, prior to that, the former student organization that strived under Sadat). The spokesman of the Al Nour party stated, “We have a great relationship with the Brotherhood, but we diverge on our vision.” This shows the nuanced and complicated relationship between the Salafis and the Brotherhood in Egypt. The parliamentary election’s results were quite surprising; with around 65% turnout, the Democratic Alliance led by the Muslim Brotherhood won 235 seats, and the Islamic bloc came second with 121 seats. They completely outscored the secular parties and grabbed a total of 356 seats out of the 498 they were competing for. In the Upper House election, with only 15% turnout, the 2 coalitions won 150 out of 180 seats possible. Another important institution was the Constituent Assembly, whose goal was to write a complete new constitution. With 50 parliamentary members and 50 non-MPs, they were selected, and just as in the elections, the Islamists (Muslim Brotherhood or Salafist of the al-Nour party) were a majority, which prompted the secular parties to protest this decision in the streets, as it would mean an Islamist constitution, while the Islamists argued that it was a completely fair selection, as they largely won the Parliament and the Upper House, and this selection reflected the will of the people. Secular parties, the Coptic Church, and Al-Azhar’s representatives in the Constituent Assembly resigned in protest, and the Transitional Government dismissed the Constituent Assembly to form a new one, even though the Islamists protested this decision. Mohamed Morsi, head of the FJP, stated, “We respect the decision and won’t challenge it.” The presidential election race started in March 2012 after pressure from the streets and protests. At first, the Brotherhood pledged to not participate in the presidential election and even excluded Abdelmoneim Abu al Futuh (a senior member of the Brotherhood) after he declared himself a candidate. They did this pledge to avoid more confrontation with the seculars and to appease Western governments. But as members of the previous Mubarak government competed for the presidential elections, the Brotherhood presented Khairat al-Shater as a candidate to oppose the old regime. But the Transitional Government had set strict rules for the election, one of which was that any candidate must have been released 6 years before presenting himself as a candidate; Al-Shater was released only in 2011 after 4 years in jail.

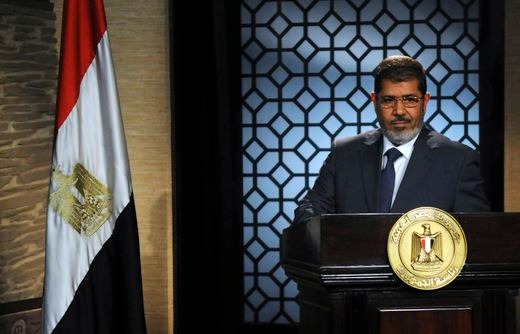

Another Islamist candidate, Hazem Abu Ismail (a Salafi who ran as an independent), was also barred from competing as the transitional government claimed his mother had dual citizenship (which, again, was forbidden for a presidential candidate), even though Hazem always claimed that she only had a green card and never had American citizenship. Al Shater was the popular one amongst the Muslim Brotherhood, whereas Mohammed Morsi was less known, but he was the leader of the FJP party and the second choice of the Brotherhood. A poll just a month before the election showed the probable winner would be either Abul Futuh (former Muslim Brotherhood, backed by the Salafis) with 32% or Amr Moussa, former minister of foreign affairs under Mubarak, with 28% intention of voting. Morsi had only 8% in that poll, as he was still relatively unknown and the last candidate to enter the race. The FJP program wanted to be more inclusive and spoke about subjects appealing to Egyptian society; it also defined Islam as a frame that would encompass the Egyptian identity and politics, but the state would be a democratic one. However, the first round of the election was surprising; in a close race, Morsi came first with 24.78%, followed by Ahmed Shafik (former prime minister of Mubarak) with 23.66%, the Nasserist Hamdeen Sabbahi at 20.72%, Abul Futuh at 17.47%, and Amr Moussa at 11.13%. The second tour would see Morsi against Ahmed Shafik, Islamists against seculars, or the Muslim Brotherhood against the old regime. However, between the first and second tours, the military transitional government dissolved the parliament, gave itself full control in matters of the army (and took that power out of the reach of the future president), and abrogated articles of the constitution’s draft. That’s an important thing to understand about Egypt: the army is a political entity. Since Nasser and his free officers’ coup, the army has been in power up until 2011. Nasser was an officer just like some of his ministers; the same goes for Sadat, and the same goes for Mubarak. Like historian Khaled Fahmy said, the modern Egyptian state is a state built for its army. And so in 2012, people expected the army to rig the elections and put in power former Prime Minister and former Commander of the Air Force Ahmed Shafik, but surprisingly, Muhammad Morsi won the second round with only 800 000 votes more than Shafik. Abul Futuh and his supporters, but also the Salafis, supported Morsi in the second tour, while a secular alliance was made around Shafik but ultimately failed.

The Brotherhood finally in power: a new era ?

Morsi had a lot of things at hand: he had to find a solution to keep power and limit the army’s influence in politics; he also had to reconcile the country, as he won only by a small margin and had almost half of the country against the Brotherhood; he had to build a state with institutions and a full constitution; and he had to address urgent issues of security, economy, and justice (as the trial for the old members of the Mubarak regime revealed, some judges showed clemency towards the old regime because they were not independent judges and were appointed by Mubarak, though he himself was condemned to life in prison for the murder of protesters). Morsi tackled small but important issues for his first 100 days: sanitation, traffic, fuel, and bread. But then, Morsi took on a bigger problem, the parliament. After initially (before the presidential election) accepting the decision of the Army to dissolve the parliament, Morsi, now president, opposed it and called for reinstating it. While Islamists and some democrats supported this decision, the secular parties opposed it and called it a “Muslim Brotherhood hijacking of democracy.” The Security Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) opposed Morsi and said their decision is final and applies to all members of the state. Just a few days after becoming president, 16 Egyptian border guards were killed in the Sinai Peninsula by a militant Islamist group (whose goal was to attack Israel). Morsi, already under pressure, used this chance to fire several officials in the interior ministry, the head of military police, the intelligence chief, etc. He also announced the retirement of SCAF leader and Defence Minister Hussein Tantawi, who was replaced by the head of military intelligence: Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Morsi also retook the power that SCAF took away from the president; while some saluted the democratic transition from a military government to a civil one, others started to call Morsi a dictator. Another event would put Morsi in a difficult position: on September 11, 2012, protesters climbed the wall of the American Embassy, raised al Qaeda’s flags and tore down the American one. They protested a blasphemous movie made in the USA, which mocked the Prophet Muhammad, and some started to call for the release of Omar Abdel Rahman (an Egyptian, a former leader of al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah, and a leader of al Qaeda, jailed in the USA).

This event, organized mostly by the Salafis of al Jama’ah al Islamiyyah (who supported Morsi against the seculars but found him too moderate), caused 2 problems: on one side, the seculars were shocked by seeing this flag raised and saw it as a consequence of Morsi’s rule. On the other hand, the Salafis were disappointed when Morsi said, “I condemn and oppose all who insult the Prophet, but do not assault embassies; it is our duty to protect our guests from abroad.” He simultaneously was under pressure from his opponents and some of his own supporters.

Nevertheless, after 100 days in power, polls showed a 78% approval rate; people considered there were improvements since he took power, and Morsi promised to improve even though he recognized he didn’t fulfill all his promises for his 100-day plan. But another incident would put a thorn in Morsi’s foot. As said before, trials were taking place to judge and condemn officials from the previous regime who were either involved in corruption and/or the killings of protesters. In a trial of 25 persons accused of the death of 11 protesters and the injuries of 600 more, the Prosecutor General (appointed by former president Mubarak) found them not guilty. This sparked outrage from the victims' families and revolutionaries, who staged protests. In response, Morsi announced he would replace the Prosecutor General, a seemingly good decision, but secular forces opposed it, as the president didn’t have the right to do this, and they accused the Muslim Brotherhood of trying to impose a dictatorship and claim more and more power. Seculars protested, and the protests turned into clashes with Muslim Brotherhood supporters. The judges announced their support for the prosecutor general and claimed Morsi threatened the independence of the judiciary institution. In the end, Morsi backed off and let the prosecutor general retain his position. But the worst was to come: the writing of the new constitution.

After a new council tasked with writing the constitution was formed, drafts were made and leaked in the press. Several articles were considered highly problematic by the secular opposition, who called to boycott the writing of the new constitution. Though the draft said that Egypt is a democratic state, with respect for the rule of law, respect for human rights, equality amongst the citizens, separation of powers, and freedom, some articles outraged the seculars. Article 2 proclaimed, “Islam is the religion of the state, and Arabic is its official language. The principles of Islamic Shari’a are the main sources of legislation.” Shari’a was defined as the Sunni Islamic schools of jurisprudence, and Article 4 established that Al-Azhar is an independent institution that will be sought for matters of Islamic Shari’a. Finally, another article stated that Christians were allowed to have their own laws in matters of personal status, religious affairs, and the nomination of spiritual leaders. Some denounced this “Islamist” constitution and compared it to the Iranian regime.

The country was in a complete deadlock; there was no parliament to validate the constitution (as the parliament was dissolved by the army, and the decision was examined by the judges, who took several months), and seculars and the Coptic Church withdrew from negotiation about the constitution. Facing this situation, Morsi took it upon himself to resolve it. In November 2012, he issued 7 articles of the constitution, which gave him power to “ensure the re-trial of people involved in the killing of protesters” and “take any measure he sees fit to preserve the revolution, national unity, and security” and limited the term for the prosecutor general to 4 years, which allowed him to sack the one in place (who opposed him) and nominate a new one. Morsi and his camp claimed they were only temporary measures until a new constitution and parliament were put in place to ensure the cleansing of the state institution, whereas the opposition (almost all presidential candidates and their parties united) denounced it as a dictatorship. Protests erupted across the country, which often resulted in clashes with pro-Morsi Islamists from all sides. The Council tasked with writing the constitution (a council boycotted by the seculars) announced in December that they had finished writing the constitution, and Morsi announced a referendum to vote for the constitution. But the judiciary institutions were divided, with some refusing to hold the referendum while others agreed. In any case, violence reached its peak in front of the presidential palace on the 5th of December 2012, with clashes between pro- and anti-Morsi groups that left 11 dead and hundreds injured by bullets, Molotov cocktails, rocks, sticks, etc… The police remained quite passive in the face of the events until the 5th of December, and the army deployed around the Presidential Palace. Morsi announced a dialogue with the opposition leaders on December 8 and called for national unity, while his party called the opposition “thugs,” “terrorists,” and “mercenaries.” After the meeting, the leaders still called for protests and called to boycott the constitutional referendum planned for the 15th of December 2012. But just a few days later, they called their supporters to vote no in the referendum. The referendum was voted in with 63.8% “Yes” out of the 32.9% of voters who showed up. After the results, Morsi still called for a national dialogue to appease and reconcile the nation, while the opposition called for more protests. As some members of the Muslim Brotherhood stated, "They want democracy only when they are in power, not when we are." When we see that the secular forces supported the dissolution of the parliament by the army, refused the Islamist majority in the council tasked with writing the constitution, and contested the results of the referendum, it’s hard to disagree.

On an international level, Morsi had different foreign politics than Mubarak, who was allied to the USA and close to the West and the Gulf countries, but under Mubarak, Egypt wasn’t a regional leader. Morsi wanted to change that; he wanted Egypt to be an important regional actor. His first visit was to Saudi Arabia (who feared a bit the arrival of the Muslim Brotherhood in power and feared the revolution). His goal was to reassure this ally and speak about Syria. He even proposed a meeting between Türkiye, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt to solve the crisis in Syria. He then went to China with around 80 Egyptian businessmen to speak about the economy and try to get investments in Egypt. On his way back from China, he surprised and even shocked some people by stopping in Iran (a country that had almost no relations with Egypt since 1979), but the visit wasn’t the beginning of a full alliance, just friendly relations, as Morsi made it clear in his speech; he denounced and criticized heavily Bashar al Assad (an ally of Iran). The president of Iran visited Cairo in return, and a meeting between Türkiye, Egypt, and Iran took place about Syria, but it didn’t solve the crisis, as no Syrian actor was present. Morsi also visited African countries, Ethiopia for the African Union summit, and Sudan, trying to reshape Egypt’s politics and role in Africa. With the West, Morsi had a nice relationship; he made a speech at the UN General Assembly in New York, travelled to Germany and Italy, and met the European officials in Brussels. His goal was to resolve the economic crisis in Egypt and gather support. When Israel attacked Gaza in November 2012, Morsi took a strong pro-Palestinian stance and also mediated to stop the attack. Hamas was also part of the Muslim Brotherhood (although every Muslim Brotherhood group is independent from each other, they don’t have the same leadership), and they were still closely linked, with Hamas leaders and delegations visiting Cairo several times, and Cairo hosting talks of reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah. Morsi tried (as he was still restricted by the peace deal with Israel made in 1979 and the military leadership) to reopen the Rafah border, or at least ease transit for Palestinians and Egyptians, thus relieving the blockade imposed by Israel and Mubarak. Morsi also had really close relations with Türkiye and Qatar.

In 2013, fuel shortages and electricity cuts were adding oil to the fire of the streets. Newly created armed groups made attacks in Sinai against policemen and the army; a Qatari official said those groups were supported by a country from the Gulf with weapons and money (maybe the UAE). Weekly protests and clashes took place throughout 2013. From June 2013 or even before, the army started to prepare their coup. On the 23rd of June, they issued a statement saying, “All the parties have 7 days to resolve the situation, or else we will intervene.” This statement was interpreted differently; for the Brotherhood, it meant the army would back the government, while for the opposition, they hoped for a coup from the army. On June 26, Morsi made a lengthy speech to make concessions to the opposition; he announced the creation of an independent committee composed of all parties to review the proposed constitutional changes. Governors and ministers must appoint assistants from the youth (as it's the youth who protest). But the opposition renewed their demands for Morsi’s resignation and new presidential elections. The army deployed in all of the capital officially to “protect state institutions.” On June 28, a huge protest in support of Morsi was organized to show support for the president and that he is not alone. On June 29, Morsi met with his defence minister, Al Sisi, to discuss a roadmap on how to solve the crisis. After agreeing on a plan, Morsi met with the parties that supported him to consult them. All agreed on the plan except the Al Nour party (the Salafi party), which made more and more demands. On June 30th, a huge protest gathered millions across the country to oppose Morsi, but even though they were numerous, the protest didn’t last, compared to protests organized by pro-Morsi, who organized sit-ins and slept in tents on Rabaa al ‘Adawiyya Square. On July the 1st, the army issued a 48-hour ultimatum to resolve the situation and carry out the will of the people, though after being confronted by Morsi, Sisi retracted the statement. The next day, Morsi met once again with al-Sisi, and both agreed to reshuffle his cabinet and nominate ministers who would be agreed upon by both the army and opposition parties. But by 6 p.m., al-Sisi sent a message to the president saying, “The agreement is off; you have to go.” Morsi wanted to make a speech, but because the television was under military control, the only solution was to film and post it on social media. On July the 3rd, al-Sisi, surrounded by several high-ranking members of the army, the Coptic pope, the Al-Azhar grand imam, the leader of the Al-Nour party (the Salafi party), and Mohamed el-Baradei (the most popular politician amongst the seculars, liberals, and democrats), announced the coup.

Their presences were not insignificant; the Pope and the Grand Imam of al-Azhar are the representatives of the religions in Egypt, showing unity from Copts and Muslims for support in the coup. Whereas the presence of high-ranking officers from different corps of the army showed the unity of the army. And finally, the presence of different political leaders was to show support from the people for the coup (the presence of the Salafi leader of the Al-Nour Party was essential to show that even Islamists were opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood and the coup was not only seculars against Islamists; it was the unity of the civil society). It also added a religious legitimacy for the people who didn’t recognize al-Azhar’s legitimacy. Because in the propaganda of the new regime, it is not a military coup; it is just the army joining and carrying the will of the people in a revolution. After the speech, Morsi and his counselors were arrested and kept in the presidential palace by soldiers before Morsi was moved by helicopter. It was the end of Morsi’s era and the beginning of a new uncertain one.

.png)