The Russian Occupation of Chechnya

.png)

Introduction: An Overview of the Chechen Struggle

While war and oppression in Chechnya may today appear to belong to the past in the eyes of public opinion, they in fact continue - more than ever - to shape the daily lives of the citizens of occupied Chechnya. Living in the mountains of the North Caucasus, at the crossroads of Georgia, occupied Dagestan, Russia, and occupied Ingushetia, the Chechen people, that counts no more than around 1,7 million individuals, are now subjected to one of the most brutal dictatorships in the world, all under a veil of widespread international indifference. Acting with total impunity, and sustained by the complicit silence of so-called global powers, today, Russia continues its genocidal policies against the Chechen people.

However, before dismantling and exposing the façade of peace erected by Russia upon the ruins and blood of the Chechen nation, it is essential to understand that these attempts at colonization - as well as Chechen resistance - are not recent phenomena. They are rooted in a long historical process and stem from Russia’s explicit desire to see the Chechen people disappear.

A History of Struggle

As early as the 16th century, driven by expansionist ambitions and the search for access to warm seas, Russia launched its first incursions into Chechen lands. This marked the beginning of a long resistance that would profoundly shape relations not only between Chechens and Russians, but more broadly across the entire North Caucasus. In the 17th century, following the emergence of the first Chechen Muslim preachers, initial legislative reforms took place, and the Chechens gradually implemented the Sharîʿah in their lands. In the 18th century, under the leadership of Sheikh Mansur, the first Imâm of the Caucasus— the people of the North Caucasus united under the common banner of Islam and rose up against Russian expansion. The Ghazot (Chechen term meaning “holy war”) was declared against the Russian aggressor.

In 1791, Sheikh Mansur was defeated and imprisoned by the Russians in the fortress of Shlisselburg, where he spent three years before dying in April 1794. However, Mansur’s death did not bring an end to the struggle against Russia. Rather, under the successive leadership of figures such as Taymiyn Biybolt, Tashu-Hadji, and Benoyn Boysghar— better known as Baysangur of Benoi, the Chechens continued to resist unilaterally, following the rapid submission of neighboring peoples and the complete absence of foreign support.

Sufism’s Place in the Resistance

Throughout the resistance, Sûfî Islâm of the Naqshbandi tarîqâh provided the ideological framework for the first political unification of the region, as it was the first form of Islam to reach Chechnya. Initially carried by Sheikh Mansur, the green banner of the Naqshbandiyyah tarîqâh came to encompass the entire resistance and paved the way for the emergence of the Caucasian Imamate, itself upheld by the Muridist movement. North Caucasian Muridism was a 19th-century socio-political and religious-military movement that combined the spiritual teachings of Sûfî Islâm with a militant struggle for independence against the expansion of the Russian Empire. The movement provided the ideological foundation of the Caucasian Imamate until the surrender of Imam Shamil in 1859. By the official end of the Caucasian War (1816-1864), the Chechen population was reduced by half, declining from 200,000 individuals to only 98,000, with hundreds of villages burnt and destroyed.

Despite the Tsarist conquest, resistance never truly faded. After the arrest of Chechen Qâdirî figure Kunta-Hadzhi and the mass-shooting of Shali in 1864, rebellion knew no truce. Between 1877 and 1878, Alibek-Hadji and his followers rose up from the forests of Vedeno. In the early 1900s, the Abrek Zelimkhan inflicted significant losses on occupation officers. In 1919, Uzun-Hajji took advantage of the Russian Civil War to proclaim the Emirate of the North Caucasus. The aim pursued by the Chechens was to restore an independent state governed by Sharî’ah, the expulsion of the Russian colonizers and to judge the traitors.

The Red Army (USSR) ultimately took unofficial control of the region in the 1920s, yet this failed to pacify the population. Insurrections continued relentlessly (1929, 1930, 1932, 1943…), and the Bolsheviks managed to maintain administrative control only over no more than 20% of Chechen territory.

1944’s Genocide: The Undesirables

In 1944, while World War II raged on, Stalin ordered the total deportation of the Chechen people to the steppes of Central Asia, falsely accusing them of collaboration with Nazi Germany. While this accusation served as the official pretext, the real justification lay in the Chechens’ persistent refusal to submit to Soviet policies, including the firm opposition to collectivization and war effort. Planned since 1943 by the USSR, the deportation was meticulously prepared. Population censuses were for instance conducted throughout 1943 to estimate the number of train wagons required, and more than one hundred thousand NKVD troops were already deployed across the occupied territory to blockade roads and prepare the operation.

Starting at 5:00 a.m. on February 23, 1944, the total deportation of the Chechen and Ingush population started. Archival reports indicate that the planned deportation of Chechens involved 493,269 individuals, while Chechen sources estimate the number closer to 600,000 people (approximately 99% of the Chechen population), rounded up into 180 train convoys. Joseph Stalin personally oversaw the deportation process, with Lavrentiy Beria, head of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), sending him confidential telegrams. On March 1, 1944, Beria reported to Stalin that more than 400,000 people had already been successfully deported. It is estimated that nearly 200,000 of the Chechen exiles died either during the journey or within the first months of resettlement.

But the deportation did not end there. The cultural and historical foundations of Chechen identity were systematically targeted and destroyed, both during the raids and in their aftermath. Libraries were burned, towers and mosques demolished and worst of all, gravestones were torn from cemeteries and reused to pave streets by the Russians. History itself was rewritten: the Chechen-Ingush Republic was erased from the map, and Russian publications were revised to eliminate any reference to the past existence of the Chechen people. The few survivors - around less than a thousand - , meanwhile, were hunted down and executed. Former Red Army soldiers, officers, women, elderly and the children- no one was spared. The ethnocide was total.

Chechen Independence and Russian Terror War in Chechnya in late 1990s

In 1957, the deported people, including the Chechens, were officially authorized to return to their homelands by decree of Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrutchev. Among the children who had grown up in exile and were finally setting foot on their ancestral lands for the first time, was a certain Dzhokhar Dudayev. In the late 1980s, Dzhokhar Dudayev served as a Soviet Air Force general in Estonia, where he famously refused to suppress the Estonian independence movement despite Soviet’s orders. This dissent earned him the respect of both the Estonian population and his own people, as it embodied a principled opposition to Soviet authority. He then resigned from the Soviet military and returned to Chechnya, where he committed himself fully to political struggle and the cause of independence. In 1990, he was elected head of the Executive Committee of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People, leading the institutional and political struggle for Chechnya’s liberation. Following the failure of the 1991 pro-Soviet coup in Moscow, Dudayev and the Congress dissolved the local Soviet government with the support of the population, concluding in the historical proclamation of independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria later that same year.

The doors of freedom were, after centuries of resistance, finally open.

This declaration was however met with an immediate response from Moscow. Outraged by its loss of what it considered to be its most valuable colonies, Russia invaded Ichkeria in 1994, initiating a devastating war that lasted nearly two years. As the conflict intensified, the scale of destruction grew: mass murders and massacres occurred, such as the one in the village of Sema-’Ashka in April 1995, where hundreds of civilians were attacked and killed within two days. Villages were razed to the ground, civilians were arbitrarily detained and tortured in filtration camps, and, in April 1996, President Dzhokhar Dudayev was assassinated, just four months before the final Chechen victory on August 6, 1996.

By the war’s end, Ichkeria lay in ruins. The capital, Grozny, was reduced to near-total destruction, with civilian casualties reaching extreme levels: on a population of around 1,000,000 people, approximately 100,000 Chechen civilians were declared dead, making this conflict the bloodiest war on European soil since the Battle of Stalingrad. Yet, the tears got rapidly covered by the resilience of the Chechen people and the deep joy of seeing Chechnya becoming finally free of tyranny. Russian forces were completely driven out of Chechnya in 1996, marking one of the most humiliating defeats in Russia’s modern history. Even more important, the victory symbolized a definitive renewal for the Chechen people with their genuine roots. After a century of communism, the time finally came where recitations of the Qur’ân filled again the air, where children were taught the teachings of the Prophet ﷺ, and where communities could gather freely to celebrate their identity. It was an era in which da‘wah no longer had to be practiced in secrecy, the law of Allâh prevailed, and religion, much like in the time of Sheikh Mansur or Benoyn Boysghar, once again succeeded in uniting an entire nation.

The withdrawal of all Russian forces from Chechnya led to the Khasavyurt Accords in 1996, while a subsequent peace treaty was signed later in 1997 between Aslan Maskhadov, Second President of Ichkeria, and Boris Yeltsin. These agreements effectively granted Ichkeria de facto independence. However, this peace didn’t last. In 1999, the Kremlin unilaterally broke the accords and launched the Second Chechen War under Vladimir Putin. Drawing on both Tsarist and Soviet imperial legacies, Putin subjected the republic to relentless and indiscriminate bombardments. By 2000, Russian forces had regained control of Grozny, forcing the resistance into the mountains, where it continued the struggle under increasingly asymmetric conditions. The war resulted in the death of a total of approximately 150,000 Chechens, within which 40,000 children. In other words, in 3 to 4 years of war “only”, more than 20% of the Chechen population was killed by Russia. In 2003, the UN declared Grozny the most destroyed city on Earth.

Meanwhile, Putin established a new pro-Moscow administration in Chechnya, marking the start of the re-occupation and the birth of one of the worst dictatorial regimes of the 21st century.

The Original Betrayal

The stability of this puppet regime is predicated upon the "original betrayal" of 1999. It was then that Grand Mufti Akhmat Kadyrov defected from the independence cause to ally himself with Vladimir Putin, at the very moment the latter was still overseeing the bombardment and massacre of tens of thousands of Chechen civilians. Motivated by a pretextual shared struggle against the threat of a supposed "Islamism" embodied in their eyes by the men of Aslan Maskhadov and Shamil Abû Idris (Basayev), the accord struck between the Kadyrovtsi (pro-Russia loyalist militias) and the Kremlin also sought to legitimize a "national" narrative that serves both Moscow’s and Kadyrov’s rhetoric.

This narrative was constructed around the Sûfî origins of Chechen resistance, that Kadyrov claims for himself. The pact thus allowed kadyrovtsi loyalists to transition from the status of rebels to that of vassals and managers of an entire territory on behalf of the Kremlin. In practical terms, the agreement granted Kadyrov’s forces a monopoly on the use of violence on Chechen soil, provided they maintained "order" by any necessary means.

Putin’s Warrior and Attack Dog

Since regaining control of the region, and in results of a rigged referendum in 2003, the Kremlin installed Akhmat Kadyrov in 2004 at the head of the newly made-up Republic of Chechnya, granting him the authority to establish a legal "grey zone" where he got a large room of maneuvre, although totally submitted to Moscow’s word. Under this arrangement, Chechnya remained a subject of the Russian Federation, led by hand-picked proxy traitors, in exchange for a fragile peace and the illusion of autonomy. This was Putin’s way to wreck, once and for all, Chechnya’s aspiration for independence.

Following Akhmat’s assassination in 2004, Mr. Putin appointed his son, Ramzan Kadyrov, as president in 2007. Ramzan has remained effusive in his praise for Putin, who has in turn described him as a "son." ‘If it weren’t for Putin, Chechnya would not exist,’ Kadyrov once said in one interview. In choosing this path, Kadyrov firmly turned his back on independence and, effectively, on the freedom the Chechen people had always cherished and fought for.

Ever since, a textbook awkward cult of personality has flourished in Chechnya just like in Shî’î Iran, Assadist Syria, North Korea and the lands of the Arabs. Portraits of Ramzan Kadyrov and his slain father adorn many buildings in Chechnya, and a parade of western celebrities - among whom, for instance, the famous football player Maradona - have visited and professed their admiration for Kadyrov since the beginning of the 2000s.

But behind the façade, an atmosphere of fear prevails.

Since he came to power in 2007, several human rights groups, like Amnesty International, have documented several abuses attributed to Kadyrov, including, for instance, the forced disappearance of opponents and cases of torture. Those who criticise official shortcomings in Chechnya are even sometimes paraded humiliatingly on local state-controlled TV. Even random citizens are subjected to these practices, and are subjugated to the daily fear of getting abducted by the regime. As it was not enough, religious practice is strongly controlled and surveilled too. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, a new form of practice even emerged: random massive kidnappings of young men over the streets. Those abducted are then forced to sign documents and sent to fight under the soiled flag of Russia in Ukraine.

That’s “Putin’s Chechnya.” An atmosphere of terror, and a deeply controlled population who’s left under one of world’s worst dictatures. To maintain the occupation and make sure no dissent emerges in Chechnya, the Kremlin directs the repression against the Chechebn people on every possible fronts: religion, memory, society, digital and diaspora.

The Construction of "Traditional Islam": A Tool for Legitimacy and Repression

When he was first placed at the head of occupied Chechnya by the Kremlin, Kadyrov’s rhetoric was void of any religious discourse and rather marked by an anti-islamic form of ideology, mixed with Sûfî/secularist aesthetics. During the early 2000s, simply having a beard was enough for the occupation authorities in Chechnya to abduct or even kill someone. The hostility toward the Sunnah is something many authoritarian regimes share. Before the pro-Russian authorities later tried to “rebrand” the issue through the construction of a so-called "traditional islam” that matches Moscow’s narrative, the occupation even used to openly mock Muslim men with long beards, calling them “gezzari” - a derogatory term meaning “goats” in Chechen.

The Rebranding

After physically eliminating or forcing into exile the majority of the leaders of the Chechen independence movement, the authorities set out to hollow out the symbols of the resistance of their political substance and reinvest them with an absolute loyalty to the Kremlin. The beard, once a motive for persecution, has become the compulsory emblem of the modern Kadyrovtsi. The current aesthetic of Chechen security forces - long, carefully groomed beards, high-tech tactical uniforms, the imagery of the “mountain warrior” and the use of nasheeds layered over their videos - is a direct copy-paste of the aesthetic of the very mujahideen of the First and Second Chechen Wars Kadyrov and his men betrayed. This mimetic strategy seeks to appropriate not only the heroic prestige associated with the figure of the Chechen resistance, but also the one of the abreks (the historical Chechen rebel warriors against Russia) and place it at the service of the Russian federal state while, at the same time, legitimizing the occupation. Yet, despite these efforts, the image never truly fits. The symbolism feels hollow and the performance forced. This behaviour then betrays a deeper truth: the occupiers are aware of the religious and moral vacuum they operate within.

This strategy of “memory marketing” has also extended to military nomenclature. In 2023, Kadyrov named new battalions destined for the Ukrainian front after Sheikh Mansur and Baysangur of Benoi, two notable figures of the armed struggle against Russian imperial expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries. This usage is particularly cynical, as it mobilizes the names of those who fought the precursor of the present-day Russian state in order to motivate soldiers to die for the expansion of that very same state in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine provided the Kadyrov regime with the opportunity to complete its ideological synthesis. By transforming “feudal loyalty” to Putin into a religious duty, Kadyrov constructed the strange and islamically baseless concept of “Jihâd for the Kremlin” which is now promoted all over occupied Chechnya. This contrasts with the "pacifism" long preached by advisors like Shakhidov, who used to order Chechens wishing to aid the Palestinian struggle to simply "stay home." Thus, since the outsets of the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, regime’s Mufti Salah Mezhiev issued fatâwâs declaring that Chechen participation in the so-called “special military operation” constituted an act of “jihâd”, and even called the invasion of Ukraine a “war for the prophet and Islâm.” While the Kremlin speaks with the language of “de-nazification,” Kadyrov and his clerics go further and invoke a “metaphysical battle” against the forces of evil. In doing so, the occupation regime tries to defend the pretense to cast itself as the sole and last defender not only of Islâm, but also of Russia’s so-called “traditional values”.

The paradox is big: fighting for his fellow oppressed Muslim people is strictly prohibited by the regime, while dying for and under the flag of his own colonizer is strongly promoted as the “ultimate martyrdom”.

Traditional Islâm ?

The promotion of the modern concept of "traditional Islâm" in Chechnya, and more widely in Russia, is far from being a re-emergence of ancestral practices or original Islâm. It is rather a deliberate and secularist political construction designed to provide a moral and ideological foundation for the Kadyrov regime and its abuses, under the cover of the “fight against Wahabism”. This Kremlin-led doctrine relies on the so-called historical structures of each Muslim lands occupied by Russia, and, in the case of Caucasian Sufism, primarily the Qadiriyya and Naqshbandiyya brotherhoods (turûq), which have structured Chechen society since the 19th century.

This promotion of Sufism, which is somehow seen as more “pacifist”, serves several strategic functions for both the Kremlin and Grozny. First, it offers an endogenous alternative to the Chechen resistance spirit and so-called radicalism (actually, the word “radicalism” is used by Russian authorities to target any practice that doesn’t align with the regime’s version of Islâm) that had gained ground during the wars of independence in the 1990s. Second, it allows the regime to discredit any opposition as being "non-Chechen" or "Wahabite" and claim for itself the “true Chechen Islâm”. Finally, it integrates into Russia’s "soft power" strategy toward the Muslim world, presenting Kadyrov as a bulwark against extremism, while facilitating relations with Gulf monarchies and other Arab states on the pillar of common struggle against “political Islâm” and “terrorism”.

To eradicate any potential "Salafist" influence in the region (here, the term includes both Madkhalî and Jihâdî movements, wrongly seen as two sides of the same coin by occupation services), the regime has hence established a ubiquitous religious surveillance apparatus. The Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Republic of Chechnya (SAM CR) - basically, another tool directed by Moscow - controls the appointment of imâms and the content of sermons delivered during Friday prayer. Consequently, the regime began systematically profiling individuals based on physical appearance, aiming in priority those whose physical appearance looked like resistant ones, and criminalizing any merely religious behaviours under the label of “radicalism”.

Thus, in occupied Chechnya, today, young men risk abduction and torture in secret torture camps for something as simple as wearing "shortened" trousers that matches the Sunnah, having hair that is deemed too long, or sporting a beard that doesn’t match Kadyrov’s norms, all of these being considered as symptoms of “Wahabism” by the regime.

Kadyrov has even specifically instructed police and local communities to closely monitor how people pray and dress and to punish those who stray from his caricature of what should be Sûfî Islâm. A September 2016 article published by Forum 18, a Norwegian human rights organization that promotes religious freedom, states with regard to both Chechnya and Dagestan:

"In the republics of Chechnya and Dagestan in particular, those dubbed ‘Wahhabis’ [Muslims adhering to a purist form of Islam critical of Sufism] – and sometimes men merely with a devout Muslim appearance – may be detained as ‘extremists’ by the law enforcement agencies. Local residents report that they are frequently tortured, and in some cases disappear, allegations very occasionally confirmed by state officials." (Forum 18, 13 September 2016)

Another example could be the one of the niqâb (or more generally what the regime sees as too “strict” hijâbs), officially banned by the Sûfî-led muftiate, which doesn’t hesitate to humiliate on national TV the sisters who bravely choose to wear it.

Despite Western media’s biased and fantasy portrayals of Kadyrov’s supposed "Islamist" tendencies, the regime's actions are in fact focused on state-controlled political conformity and completely depend on what Moscow allows or not, and, so, not on any Islamic principles. Actually, Kadyrov even stated in numerous interviews that there is no need for Sharî’ah in Chechnya, and that the Russian Federal Constitution is “enough” as source of legislation.

The Pinnacle of Submission to the Kremlin: The 2016 Grozny Conference

The culmination of this "traditional Islâm" promotion was the international conference in Grozny in August 2016, titled "Who are the People of the Sunnah?". Sponsored by Kadyrov with Putin's endorsement, the event hosted over 200 scholars, including the Grand “Imâm” of Al-Azhar. The objective was to redefine Sunnism to explicitly excommunicate Athariyyah, or, as they call it, Wahhabism, from Ahl-Al Sunnah Wa-Al-Jamâ’ah, classifying it as a "dangerous sect" and "anti-Islamic."

The conference ended with the following declaration by the current Sûfî Mufti (appointed by Mubarak) of Egypt, Ahmed El-Tayeb who defined Sunni Islam as follows:

"Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jama’ah are the Ash’arites and Maturidis (adherents of the theological systems of Imam Abu Mansur al-Maturidi and Imam Abu al-Hasan al-Ash’ari). In matters of belief, they are followers of any of the four schools of thought (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i or Hanbali) and are also the followers of the Sufism of Imam Junaid al-Baghdadi in doctrines, manners and [spiritual] purification."

The irony is profound: a congregation of so-called scholars, many sent by their respective governments and serving nothing but their political rhetoric, attempted to claim a monopoly on theology in a land under the control of a dictator acting himself as Putin’s regional “war dog”. "Peace-loving" Sûfî leaders gathered at a conference held in an occupied land and sponsored by the very figures responsible for regional devastation and the killing of hundreds of thousands of Chechen Muslims. They claim to be true followers of “pure Islâm”, yet have all responded and said ‘labbayka’ to dictators who have more Muslim blood on their hands than all the greatest tyrants of the last centuries could.

And no, the aim of this article is not to defame and generalise all Sûfîs, in fact, authentic and true sufism (asceticism) is from Islam, and is known under the name of Tasawwuf or Zuhd. However, pseudo-Sufism, i.e Quburism (grave worship), and other heresies are not from Islam and have often paved the way for more heresies rather than for any benefit, notably in the form of Shi’ism. That’s the reason why we can see the enemies of Islâm, i.e tyrants like Putin and Modi, promoting Sufism (just like they support some forms of pseudo-Salafism) against so-called radicalism, the latter being, in most of cases, called as so by these leaders to describe simple dissidence from their own theological narratives.

Hardcore Repression Against Atharîs

The Atharî Da’wah is officially banned by Putin; the republic authorities have repeatedly and openly said, particularly in Chechen-language media, that ‘Wahhabis (i.e Atharî/Salafîs) are not to be allowed to live in Chechnya and indeed should be killed.’

An April 2016 commentary of the Centre for Eastern Studies (Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich, OSW), an independent public research institution analysing socio-political and economic processes in Central and Eastern Europe, describes Chechen leader Kadyrov’s stance towards Atharîs:

"One factor that is stoking the present phase of the conflict between the various branches of Islam in Dagestan and Ingushetia is the interference from Kadyrov, who wants to be seen as the one who protects ‘real’ (i.e. Sufi) Islam in the Caucasus from Salafism/terrorism. An unprecedented meeting (majlis) of representatives of twenty-four factions of Sufi brotherhoods (representing both Naqshbandiyya and Qadiriyya) from Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia was held on 2 February 2016 in Grozny. Its participants passed an ‘anti-Wahhabi’ declaration in which they undertook to refrain from maintaining contacts with representatives of Salafism. During the congress, Kadyrov announced he would combat ‘Wahhabism’ across the Caucasus and even across Russia, thus expressing his readiness to help out the governments of the neighbouring republics, which was, in fact, a threat that the conflict would be escalated. Both he and his milieu (including the mufti of Chechnya, Salakh Mezhiev and the parliamentary speaker, Magomed Daudov) have issued numerous threats to Salafi leaders (mainly from Ingushetia).” (OSW, 4 April 2016)

This was the ‘Sunni’ conference sponsored by Kadyrov, a brutal dictator who rules through fear and oppression. A conference void of any barakah; its location couldn’t be worse (occupied land) and its sponsors couldn’t be worse (Putin and Kadyrov). For Kadyrov, the goal of these theological maneuvers is twofold: to assert his status as the de facto leader of Russia’s Muslims, and to delegitimize the ideology of North Caucasian resistance groups by dissociating it from "authentic Sunnism". The Grozny conference recommendations included a ban on Salafism in Russia and the creation of study centers to refute extremist thought, effectively transforming the initial theological dispute into a repressive state policy.

Revisionism and Attempts to Erase Memory

In a frantic quest for legitimacy, the puppet regime does not merely instrumentalize religion; it goes so far as to destroy the memorial heritage of the Chechen people and rewrite history to serve the pro-Russian narrative.

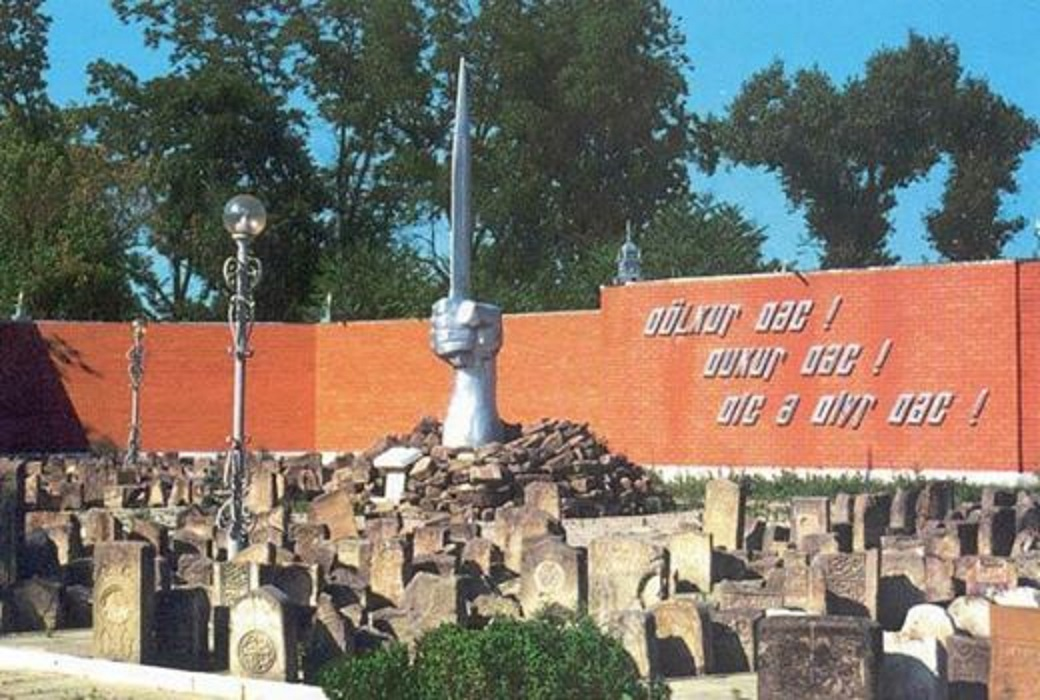

This erasure of memory was particularly violent in the dismantling of the Memorial to the Victims of the 1944 Deportation in Grozny. Inaugurated in 1992 under the presidency of Dzhokhar Dudayev, this monument was a profoundly symbolic work in the eyes of the Chechen people, who finally saw the hundreds of thousands of victims of the tragic deportation of February 23, 1944 honored as they deserved. The structure consisted of hundreds of churts (traditional gravestones) that Soviet authorities had torn from cemeteries after 1944 to use as construction material for roads, bridges, and pigsties. At the center of the monument stood a clenched fist gripping a saber before an open Qur’ân, bearing the inscription in Chechen:

Doelkhur dats! Dukhur dats! Dits diyr dats!” (“We will not shed tears! We will not be broken! We will not forget!”).

In the late 2000s, Kadyrov’s regime orchestrated the destruction of the memorial in several stages. In 2008, an initial attempt at demolition was halted by protests from human rights defenders, after which the site was officially fenced off to remove it from public view. In February 2014, on the eve of the 70th anniversary of the tragedy, the memorial was secretly dismantled on “orders from above.” The gravestones were relocated and incorporated into a memorial complex on Akhmad Kadyrov Square, surrounded by steles honoring pro-Russian Chechen police officers killed in combat. The maneuver could not be more perverse: the memory of the Stalinist genocide is now diluted within a narrative of military glory serving the colonialist agenda of the Federation, in order to erase the memory of a whole Nation.

Alongside the destruction of monuments, the authorities also imposed a change in the date of commemoration. Historically, February 23 was the national day of mourning in Chechnya. However, this date coincides with the Russian “Defender of the Fatherland Day,” celebrating Soviet and Russian pseudo-military heroism. In 2011, Ramzan Kadyrov officially banned any public commemoration of the February 23 deportation , requiring the population instead to celebrate the communist holiday. One might ask: what harm could come from allowing people to express their feelings on this day? Yet the FSB fears that such gatherings could fuel anti-Russian sentiment, leading to a blanket prohibition on any independent commemorations. Meanwhile, in the Aukhovsky district, in South-East occupied Chechnya (currently part of the Republic of Dagestan), residents continue to mark the occasion freely and do so every year. Similar demonstrations also take place every year in cities such as Strasbourg and Oslo in Europe.

The repression of memory did not end with the erasure of physical monuments; it extended to individuals who sought to preserve and articulate this forbidden past. The case of Chechen political activist, human rights advocate, and former Ichkherian official Ruslan Kutaev characterizes this broader strategy quite well. In February 2014, Kutaev co-organized an academic conference to mark the 70th anniversary of the deportation. This initiative ran against Kadyrov’s policy of not interfering with the Russian state celebrations. The day after the conference, Kadyrov summoned the participants and publicly reprimanded them. Kutaev, who refused to submit to this intimidation, was arrested shortly thereafter on fabricated charges of drug possession. In reality, he was taken to the basements of the presidential administration in Grozny, where he was subjected to electric torture and severe beatings. Despite the absence of credible evidence and the visible signs of torture on his body, he was sentenced to 4 years in prison. The memory of the deportation was then officially seen as a form of “state property,” and anyone who attempts to invoke it outside the official framework exposes themselves to physical violence and imprisonment.

Within the framework of historical revisionism imposed by the Kremlin and relayed by the Grozny regime, one can also notice how the figure of Akhmad-Khadji Kadyrov has become the central pillar of a full-fledged state hagiography. Presented as the “First President” and the providential savior of the nation, he is portrayed in school textbooks as the man who put an end to the chaos of the two wars by choosing the path of alliance with Vladimir Putin in order to spare the Chechen people from annihilation. This narrative deliberately not only claims factual historical lies and turns a blind eye on his betrayal, but also systematically obscures his past as an independentist who, during the first war (1994-1996), openly called for ghazot against Russia, retaining only a “cleaned” image of a so-called peacemaker.

The school curriculum, structured around what is termed “The Path of Akhmad-Khadji,” thus deforms history into a lesson in absolute loyalty to Moscow. Any former aspiration to independence is reclassified as a form of foreign-inspired terrorist deviation - or even actually not taught at all in most schools - while submission to Moscow is presented as the natural and culmination of Chechen identity. This omnipresent cult of personality within the education system clearly serves the purpose of enforcing mental colonization and, by extension, legitimizing the hereditary transfer of power to his son, Ramzan Kadyrov. The ultimate goal then appears to be the complete and definitive erasing of any alternative memory of the resistance and independence-driven aspirations that marked Chechen history for centuries.

.png)